Brain Surgery

Believe what’s going on in your body, whether or not there’s a neat explanation.

Hi Friend,

How is your body feeling these days? And also, (META QUESTION ALERT) how does a question about your body’s feelings make your body feel? For me, all body talk is fraught and a little scary — like, uh oh, this is either going to be a conversation about calorie restriction, abortion, or Bessel van der Kolk.1

Here’s why this is on my mind: (1) The “fall colds” are starting to sweep through every corner of my life (and mostly my email box, in the form of, “Sorry, Professor, but I can’t see myself coming to class today, as I am very very sick”); and (2) a brain surgeon came to our writing class yesterday.

I don’t know that I can make the weirdness of the brain surgeon seem less weird. At school, it’s “Connections Week,” which means that we bring in a bunch of people in writing or writing-adjacent professions / schools / programs to talk to the young creative writers about the futures potentially in front of them, and offering ideas of paths they can take if they want to be novelists or screenwriters or people possessing graduate degrees that they aren’t 100 percent sure what to do with. Last year, some of the students expressed that they didn’t actually want to go into writing fields, creative and writerly as they might appear. Hence, I guess, the brain surgeon.

The brain surgeon is friends with my boss. It’s hard to believe that she had any time to come speak to unfamiliar teenagers on a Tuesday afternoon, but there she was. She was late, and she apologized, adding (with great humility) that she was coming off a 40-hour shift at the hospital. Had I been anywhere for that amount of time, there would be no level of intrinsic do-goodedness (or even cash money) that would persuade me to be anywhere but my own bed, but the brain surgeon is a better person than I am.

She had come with a PowerPoint presentation that included not only the logistics of what it takes to be a brain surgeon (over a decade of school, plus at least half a million dollars), but also pictures from her life — driving a green Land Rover, vacationing in Florida, celebrating birthdays, hanging out with her friends. She included a picture of her wife when they’d just met, and one when they’d just gotten married — both in long, white dresses and tennis shoes, dancing along a city crosswalk on a sunny day. The point was: there’s no way around the hard work, but as you’re moving through it, a life unfolds. The life happens inside the work, but it is not equivalent to the work. It requires paying attention to all the potential in the margins. I was struck by the fact that even in something like neurosurgery, there were margins. It isn’t a point that is always salient on “Grey’s Anatomy.” (Although, there is definitely a lot of sex happening in closets on “Grey’s,” which I suppose is sort of marginal in its own way.)

Anyway, the presentation was magnificent, and it felt criminal that more people didn’t get to watch it. (Because also, the brain surgeon is a gay Latina from an immigrant family, and as she emphasized, this is remarkably uncommon in neurosurgery. She added, too, that “I am still the only one in my practice” who can speak fluent Spanish with patients. I think more people should see and hear all of this.) But the best part was after her PowerPoint, when we were allowed to ask questions.

A student asked what made her decide to choose the long and intimidating path of becoming a brain surgeon, and she offered a story — the kind that would be in a movie about this kind of life — about dissecting a fetal pig in high school. She said that they didn’t get to cut into the pig’s brain in class, but that when she expressed interest in it, her Biology teacher said she could come back at lunch and do it on her own — which our hero, the brain surgeon, did. And, she said, looking at the brain, she had this thought: “This is amazing. I want to be a part of this.”2

As she told this story — and sorry to get cliche here, but there’s no other way to describe it — she lit up. The students noticed, and more hands shot up with more questions. Someone asked next, “What is your favorite part of the brain?”

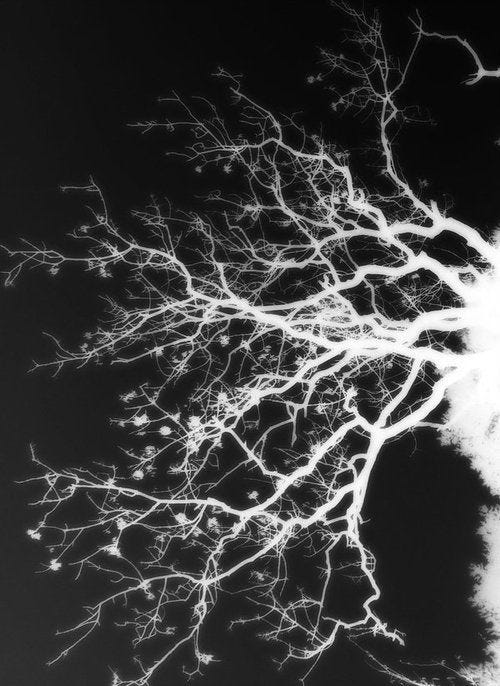

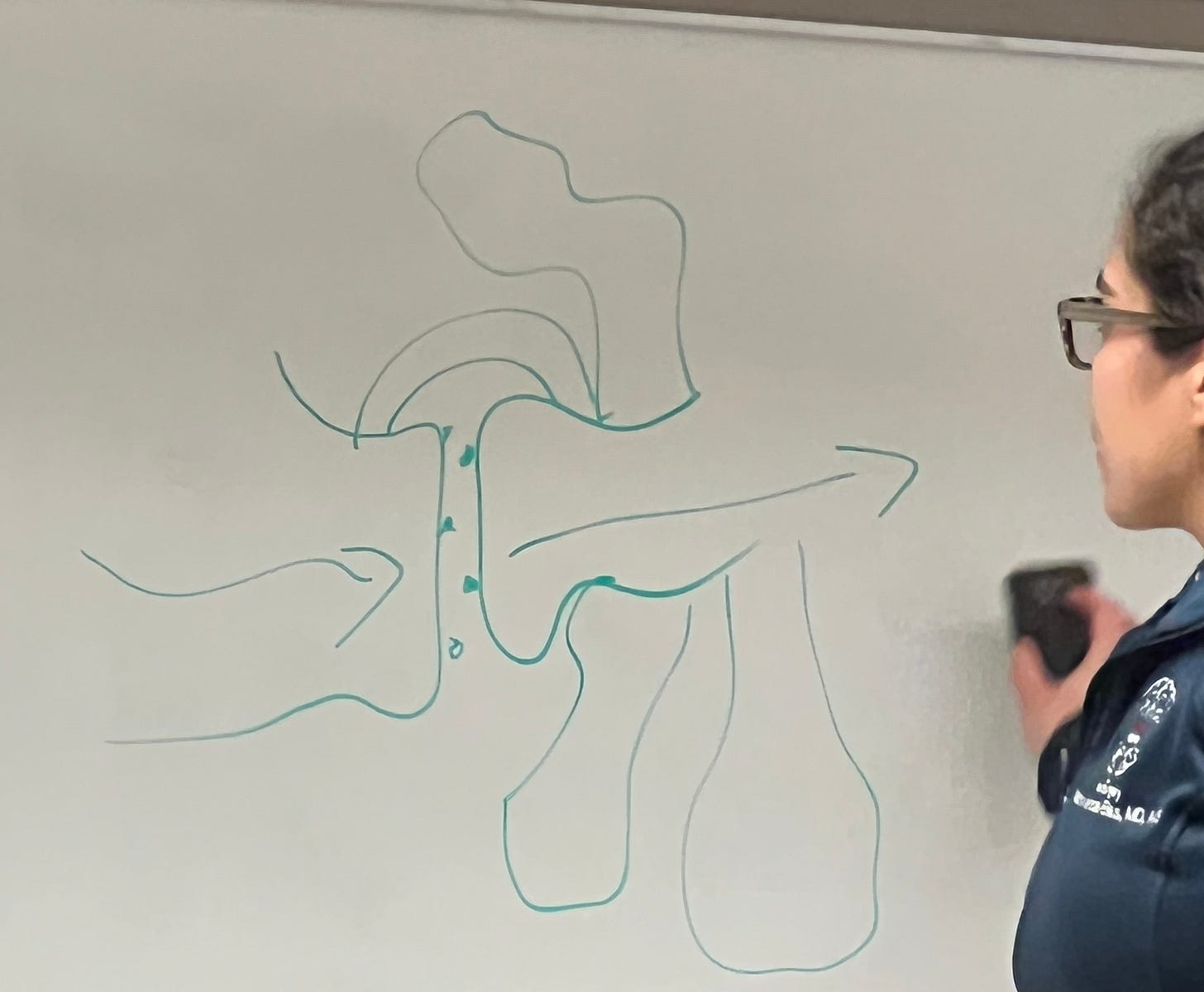

The brain surgeon took a sip of water from a plastic water bottle, like you would if you had quite a lot of thoughts you had to gather. She said, “Here’s the thing: Brains are AMAZING.” She had more than one favorite part. There wasn’t time to talk about all of the parts and how amazing they were. But she Googled some photographs of iodine-dyed fibers coming off the brain stem, and when she pulled these up, she looked like a person who had only ever seen shades of gray glimpsing a the Hudson valley in fall in CMYK. This was particularly profound because these are pictures that she looks at all day, every day, and she was still so filled with wonder. She said, “I think the brain is the most beautiful thing.”

I wrote in my journal, “The brain surgeon thinking the brain is the most beautiful thing is the most beautiful thing.”

I wished you could’ve been there; or that I had known that this was a moment I should have been videoing. There were other answers she gave that were not beautiful so much as they were illuminating — because, as you know, brain science is popular. Psychology pop science books are everywhere, and I am not immune. I loved the brain science in both Emily Nagoski’s books; I love when Tara Brach talks about it, too. Bessel van der Kolk’s “The Body Keeps The Score” is all about brain science, and appeals to people who want proof; anyone can come up with theories about why we behave the way we do, but not everyone can show us pictures of our brains. The pictures and the years of scientific training translate, to many of us, to truth.

A student asked two questions in succession that spoke directly to where pop-science is these days — these are Instagram-friendly ideas that I myself have written about after reading a study or two in Psychology Today. The first question was, “How does accumulated trauma show up in the brain, and how does it affect our lives?”

This is a huge and hard question, and I thought maybe the brain surgeon would say so, but instead she said, “That’s a great question. And the short answer is that we really don’t know.” She went on to explain that science around PTSD is somewhat new, and that most longitudinal studies about it are about people who’ve fought in wars, since those are the people who, for a variety of reasons, are easiest to study. The thing we know, she said, is that “it affects us a lot.” We should be wary of trying to explain it much more than that in 2022; but we know for sure that trauma changes our bodies.

Then the student asked, “How does neurodivergence show up on brain scans?” The neurosurgeon said, “It doesn’t.” She explained that the term “neurodivergent” is still being defined, and it currently means a lot of different things. Since the word is so broad, it’s impossible to study. That doesn’t mean it’s not true that people don’t experience differences in how they think; it just means that the science isn’t caught up with all the ideas floating around on these subjects, and that it probably won’t be for a long time.

I appreciated this perspective; it was refreshing to hear someone answer questions about science who cared about the answers, but wasn’t trying to sell an idea or a theory. It reminds me that the scientific method as we use today is itself relatively new (it was developed in the 1930s), and that what we understand about bodies and brains is actually fairly limited.

It’s reassuring when someone says, “The cold weather and the changing leaves are cueing your animal body to rest more, and so you need to take more time to sleep and shelter than usual this time of year” (I believe this to be true, by the way); or, “Commuting every single day when you’ve had some scary experiences on trains in the past is actually triggering and exhausting and harder on your body than you know” (I believe this, too); or any iteration of, “Here is a reason you feel bad right now. This is science. It makes sense.” I appreciate how much we crave to understand and explain why our bodies do the things they do and feel the things they feel. The challenge I have for you is to focus on this absolute truth, which is just a letter off from the comforting statement. “THERE is a reason you feel bad right now. This is science. It makes sense.”

Whatever discomfort you’re having right now, you’re not making it up. It’s not your fault. You don’t need an explicable excuse for your body to be telling you something. (Something we also know for sure about brains is that emotions are physical; you can’t “think your way” out of them. They are physiological processes that need to complete their cycles.)

I wish we could all regard our own bodies and brains the way the brain surgeon regarded the image of the brain stem: with total amazement and wonder. It’s hard to do when you read about how your body is “supposed” to be — we’re all too ourselves to ever feel entirely like we fit. Whatever it is you’re feeling, it’s real — whether or not there’s a neat and simple explanation.

I often doubt my own experiences. I shouldn’t be stressed if other people are not stressed (and they’re working harder!); I should be thinner because other people my height are thinner; I’m probably not actually sick, since I don’t have a fever; I must not be tired since I got enough sleep; my sadness is irrelevant because nothing that bad (or bad at all) happened to me; and on and on and on. This kind of thinking stopped me from going to the hospital when my appendix burst. But science can only explain my body to a point; there is so much that is still completely mysterious — and the mystery of it doesn’t make it any less true.

This was said to me by a literal brain surgeon. So if you recognize yourself in anything written above, please: listen.

Love,

Sophie

Parenting Paragraph

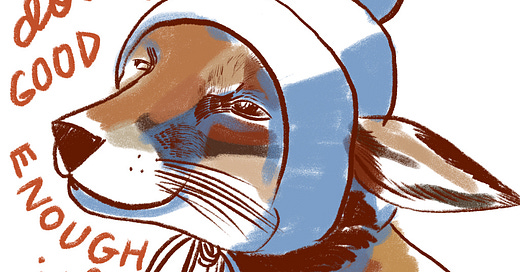

I think I’d better write about T’s helmet. If you’re a long-time reader, you’ll remember that it’s been months since our pediatrician first suggested that T would benefit from a helmet, because she lay on one side of her head too much as a baby and her head ended up sort of flat. I don’t think it’s terribly noticeable, but other people have noticed, and apparently this can lead to asymmetrical facial features in adulthood, which I guess are aesthetically disappointing? IDK, it seems fine to me — but it might not seem fine to grown-up T. The window was short to act on the helmet, and after lots of conversations with lots of people, we decided to go for it — with muttering of, “We wouldn’t want to regret anything.” The helmet is $4,000 and change. The appointments to see the helmet guy are $500 each and take place every two weeks for several months. The insurance covers none of this. We are SO PROFOUNDLY PRIVILEGED to be able to say “yes, we’ll pay” (we were able to refinance our house), and I am totally aware of that — and still, I fucking hate this helmet. I feel shame for my hatred of the helmet. I feel shame about the helmet in the first place. Most people don’t know what the helmet is all about, and so they have stopped saying “hi” to T when they see her — people like to greet babies, but they seem scared of babies that don’t look the way they think babies are supposed to look. The only people who say hi anymore are people who know what the helmet is about, and then they just want to talk about the helmet. “Oh, my niece had to have one of those.” Or, “Some babies just don’t like tummy time, no big deal!” (BTW, T loved tummy time! But whatever.) Beyond the publicly facing deficits of the helmet, T wears it 23 hours a day, and I miss her head. I miss kissing it. I miss her ears. I miss her smell. I miss letting her fall asleep on me (impossible with a helmet). I’m angry that the last few months of her “baby”-hood (before toddler-hood takes over) are ones where I don’t get to hold her as close or kiss her head all day long. And look: I know this is not really a big deal, but this is the truth of the matter, and I’ve been so generally sunny about parenthood lately, that I thought I’d let you in on this particular frustration.

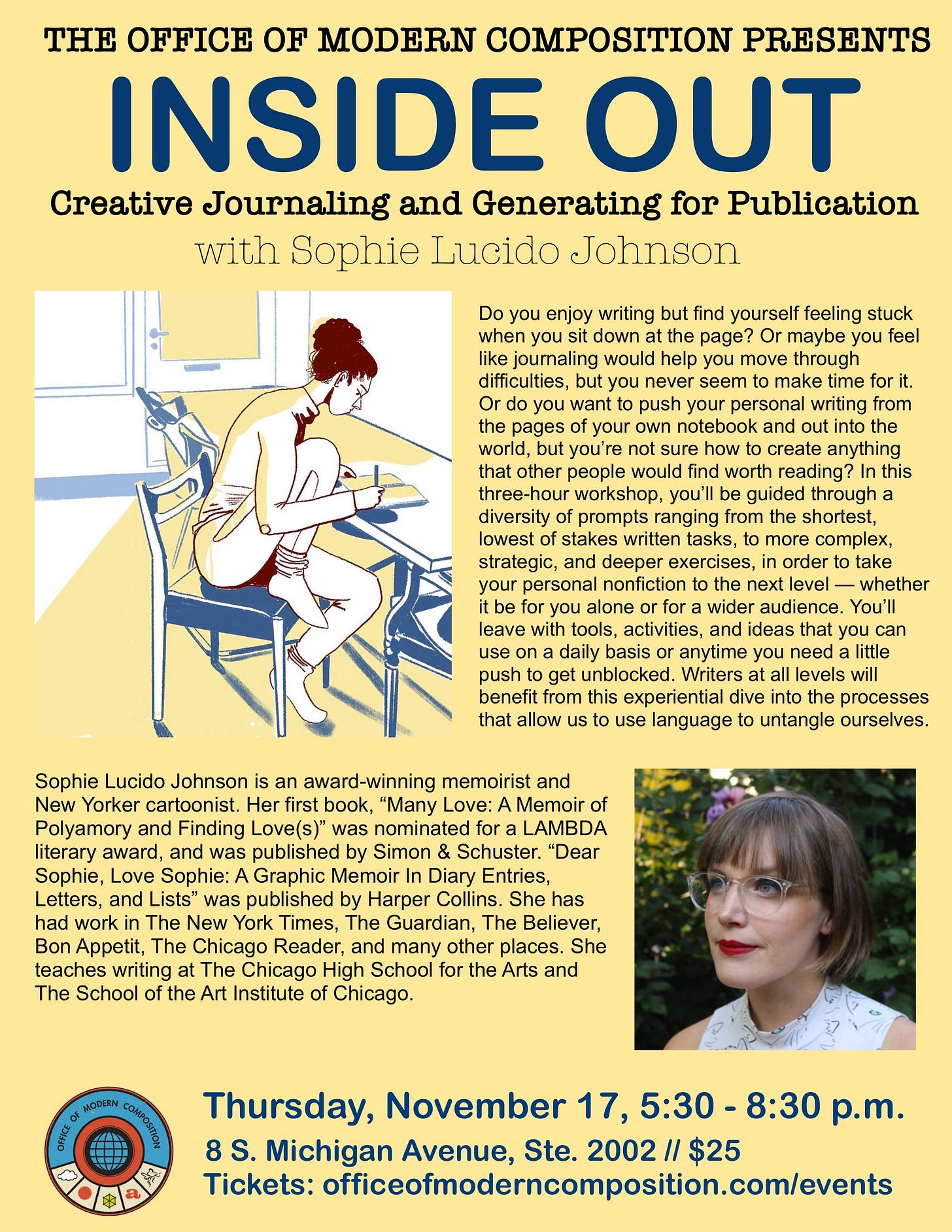

This week in Sophie

If you live in Chicago, consider joining me for a small-but-really-fun writing workshop in November! It’s just $25 because The Office of Modern Composition (where I work) is in the beta stage of these workshops, so get in on the ground floor while you can! There are only eight spots; downtown Chicago; treats provided.

I know that “The Body Keeps The Score” is a perennial favorite, and I’m really glad it has helped so many people understand complex trauma. I found it to be too sexist (and a little racist) to be really readable, and I think that this proves that actually, I am over-sensitive. I can almost never stomach a book by a white man, and I know that this is absolutely a fault of mine, but there it is: an area where I’m trying to work to be a little less judgey. Bottom line is that I don’t really like to talk about this book.

When I dissected a fetal pig, it helped me to realized that yes, I am definitely a vegan. Also, we DID get to cut open their brains, and my pig’s brain had turned to mush. After the brain surgeon’s presentation, I asked her to explain that to me, AND SHE DID. A part of me that had been forever unhinged could finally rest. (And if you desperately want to know what happened to my pig’s brain, you can email me. I will tell you.)

I find it so invigorating when people have the absolute right job and it brings them joy. It sounds like the neurosurgeon loves her job which is amazing because I would not love that job and I think it would be a bad fit for so many people. I’m grateful for people who love being neurosurgeons!

The instagram post about animals in winter is how I found you a year ago, so it's especially dear to me and I was so happy to see it. And my husband reminded me of it just last week, since we live way up North and Winter is so Coming. But here's what I wanted to say: Our youngest had something wrong with her hips (nothing too serious) (but serious enough for me to absolutely not know the English word for it) and wore a sort of hard plastic dungarees for four months, that turned her into a little square and made nursing difficult, if not impossible. This was not cancer. Or the least bit dangerous. It was just impractical and a bit annoying, but yes, I cried over these hard-hat-trousers and hated them fiercely. For all of the reasons you hate your daughter's helmet. And I felt shame for doing so, but still did it. They were shite. After four months they were removed and she was fine and her hips in the right place and I forgot all about it and never looked back. Until today, reading about your feelings about the helmet. So here is some love and understanding coming your way. You are doing a good enough job. ♥️