A Note For You, If You’re Having A Bad Day (Or, At Least A Day Where You Are Curious About Book-Writing)

Dear Friend,

You may have noticed that there’s been less of me in your inbox for the past six months or so. I have had less time for everything. In January, I declared that I was no longer available to make plans. This felt cruelly ironic: I was canceling all my plans with friends to make room for the writing of a book about how important it is to prioritize plans with friends. Days became nights became days, and more than once I completely forgot what month it was. It was a type of overwork that I’ve not faced since I was in my very first year of teaching. And even then, I wasn’t a parent. Back then, I could order a calzone and eat it under the covers as soon as I got home. (Which I did, four times per week.)

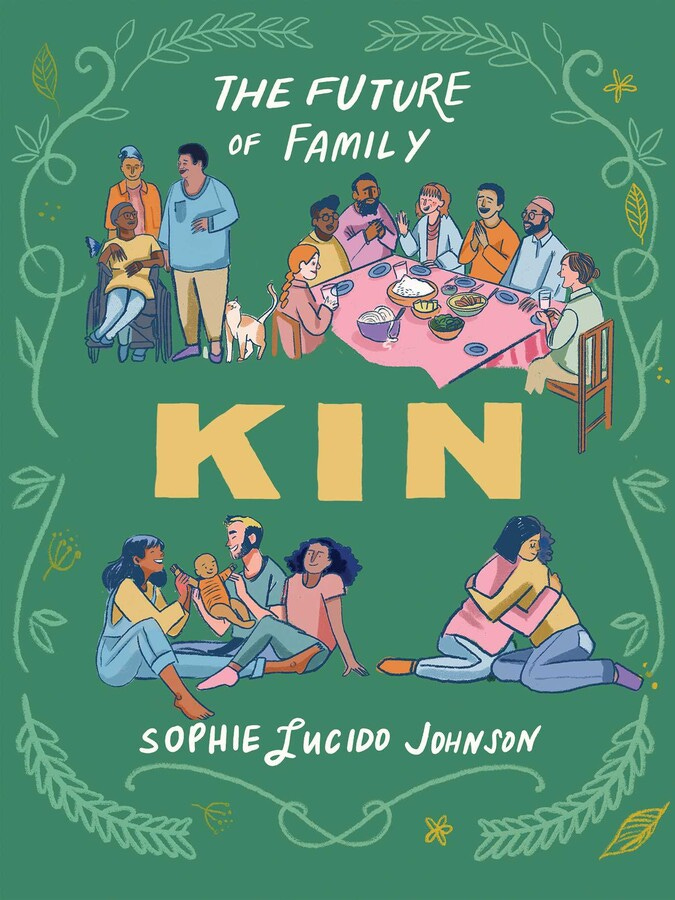

But as I compose this letter to you, the writing of the book is done. The drawing of the pictures for the book is done. The major edits have been made. The massive Word document titled “KIN” has become a gorgeous PDF titled “KIN,” with the pages formatted so that they look like the pages of a book. Because this is a book. Soon I will hold this book in my hands.

The stage I’m at now is called “First Pass,” which is where I read the whole manuscript, beginning to end, and make whatever minor changes still need to be made. (There are a lot. But they are minor.) After I’ve returned these pages, the work shifts from insular and private to exterior and public. Instead of writing the book, I will be marketing the book! Which is its own full-time job, really; but at least I’ll be talking to people.

Candidly, marketing the book is what I am doing right now. I am writing a newsletter about the book at least in part because I hope that you will be interested in the book and buy the book. I am using this newsletter as a “cover reveal,” which is a big part of the marketing campaign. It’s about to happen.

Before it happens, though, I want to be clear that the purpose of this particular newsletter is not solely, or even mostly, about marketing. It’s about demystifying the process of going from “I have an idea” to “I am holding my own book.” There are lots of essays and tutorials about this, but I have never found them superfluous, because everyone’s unique experience adds to the collective imagination of how a book might come to exist.

My favorite story I heard on an episode of ologies, and is from this woman named Anne Copeland who wrote a book called Pumpkin, Pumpkin. The author says that she wrote a first edition of the book in 1986 and sent off query letters to publishers; then she started keeping a chart of the publishing house’s responses. She was rejected six hundred times before she sold her book. And now it’s in its third printing! (And I own a copy, and it’s great. Truly. Buy Pumpkin, Pumpkin.)

Why A Book?

KIN is my fourth-ish book. (My second one, Love Without Sex: Stories on the Spectrum of Modern Relationships, was an Audible original and wasn’t released in a paper volume. But boy, was it ever a book-amount of writing.) After I wrote and published my first book, Many Love, I felt hooked on the whole process.

What I didn’t know I’d love so much about the experience was the collaboration. It was wonderfully dizzying working with editors who took the thing I wrote and had ideas for making it better. The first book editor I ever had shredded my initial draft to ribbons, declaring that I would have to re-write two thirds of it. I was miserable when I got that news, but she was also totally right, and sometimes I imagine having published a version of my first book that looked more like its first draft. The first draft had really long, navel-gazing chapters about ex-boyfriends, mostly written, I can see only looking back, to personally process the fallout of those breakups. Thank God that is not the book that is out in the world. Instead, I am mostly proud of my first book — though I think it was and is sometimes misunderstood.

After I wrote the one book, I wanted to write more and more and more books. The scope of the project; the people on your team, actively rooting for you; the creative doors you can open because people are invested in reading a work in progress. The whole ordeal felt very much For Me, in a way that being pregnant is very much Not. (These two things both are and aren’t comparable; but some people hate writing books and some people love being pregnant. We are all different!)

If you are interested in writing a book, I think you should do it. Here’s the story of this one.

How Do You Know An Idea Is A Good Idea?

You don’t know an idea is a good idea. I literally cannot enumerate for you the times I have had an “ah-ha!” moment around an idea, sure in my gut that the idea had traction, only to find out I was utterly, utterly mistaken. KIN was idea number four from me following Dear Sophie, Love Sophie. My agent, Mackenzie Brady Watson, took many phone calls with me, gently explaining why my Latest Good Idea was less good than I thought it was.

Something did feel special about KIN: a book about the ways in which the nuclear family model is failing us. I have hesitated in general to write much about the specifics around my life as a mother — mostly because other people can write much better than I can about this topic, and partially because I don’t want to write too many details about a person who can’t consent to having them published. But there are moments in life that fundamentally change your life-view, and being pregnant alongside my friend Bethany while we lived in the same house during the height of the pandemic was pivotal for me. I longed to write about the unwritable magic of that time. I wasn’t sure how this was going to look, so I protected the idea for a while.

By which I mean: I shared my seedling of an idea with only one person: my friend Jill, who I knew would lock it up in a warm greenhouse and refuse to let harm come to it. As I figured out what the idea was, I only took calls with Jill, who encouraged me to “romance the idea. Saunter up to it. Flirt a little bit.” She discouraged me from writing lists and outlines. Instead, she wanted me to handwrite on a clipboard in a car looking out at Lake Michigan. To ask questions without answering them, and fall slowly in love with whatever stuck to the sides.

Jill has done this for me on many occasions, and it is necessary, I think, to have a person like this in your corner. Later, after the thing is stalky and sprouting off in too many directions, it will be good to have a master gardener come in and ruthlessly clip errant stems. In the beginning, you need sun and space. Let someone tell you that you’re brilliant. If you don’t have someone to tell you you’re brilliant yet: find them. (I’m good at this role, too, by the way. You could always ask me.)

Three months into dating my idea, I decided that I knew it was good. Then I took it to Mackenzie. And she knew it was good too.

Composing The Proposal

This is where we really enter the territory of mysterious book things I didn’t know before I wrote a book. First, when you pitch a novel, you generally want to have the whole manuscript complete before you submit a pitch. When you pitch a nonfiction book, you want to have one really good chapter.

The proposal you send to publishers is a monster document, and it includes way more than an elevator pitch and a sample chapter. Here’s what was in my proposal for KIN, and how many pages each section spanned:

About the book: 17 pages. Ultimately, a version of this might become the introductory chapter of your book, so it’s doing a lot. You want it to immediately give the reader a sense of your voice and your vision. Mackenzie usually goes through this section and bolds the big ideas, which is a good move: it lets readers skim a bit and know what you’re really hoping to convey with the book. My “about the book” sought to answer the questions: Why this book? Why now? Who is it for? And why am I the right person to write it?

Chapter outline: 19 pages. This is a bulky section, and it has historically required the most revision on my part, because it needs to be thorough and detailed enough to prove that there’s plenty there to sustain a whole, meaty chapter. My book originally had 12 chapters, so each chapter gets a little more than a page of explanation. I used research here, and explained who I’d be interviewing in each section.

Sample chapter: 17 pages. The first sample chapter I wrote for KIN was rejected by Mackenzie, and while I was bitter about it at the time, I now feel grateful that she didn’t let me submit it. I was so terrified about not writing a serious-enough book that I wrote a chapter that was gluey and thick, about the science of friendship. When I returned to my original sample chapter six months later, I cringed. Just because you have a lot of research doesn’t mean that something is good or even readable! We went with a sample chapter about, loosely, how people should be more like bees. You’ll have to read the book if you want to know what I mean — this chapter did, indeed, make it into the final cut.

About the author: 5 pages. I wrote mine in first person and led with my biggest accolades (New Yorker cartoonist!), then moseyed into some light autobiography about my work as a teacher, etc. Most of these pages are where I list the people I know who are celebrities (Hi, Cole Escola!), who I could reach out to when it came time to market the book.

Publicity and marketing: 3 pages. This is a tough pill to swallow, but, unless you are already a big name, you will probably have to do most of the marketing and publicity for the book yourself. This sucks for pretty much every writer I’ve ever met – all of us preferring to sit in corners with laptops, “letting the work speak for itself.” But the work is not very loud, and the market landscape is always set at a deafening pitch. So you have to say how you are going to work to sell the damn thing.

Competitive works: 3 pages. The point of this section is to say what books are kind of like your book, and to prove that they’ve sold well. Some books I loved got cut from my initial pitch because they didn’t sell well enough.

Writing selection: 1 page. I added a page at the end with links to some of my favorite and best-performing pieces of writing so the publishers could have easy access to more of my writing if they needed it.

Total page count: 66 pages. WHOA. That’s longer than any paper I wrote in grad school! And the book hasn’t even really gotten started yet!

Doing The Research

So let’s say you sell your nonfiction book (yay!), and it’s time to sit down and write it.

Here is my truth, and it may not be your truth: research can trick me. I can think to myself that I have to gather things before I start writing, and then the starting of the writing never happens. Instead, I go down rabbit holes trying to find new and interesting information, and eventually I’m interviewing someone for two hours about people who have sexual fetishes around animal claws. (A not untrue story.)

For this book, which I wanted to include meticulous research, I got caught in this trap for an embarrassingly long time. At some point, I realized that the writing of the book needed to get started. I’d read a lot of books, talked to a lot of people, and transcribed a lot of interviews. Most of what I read and learned in that first stretch didn’t make it into the final draft.

I tell students to try writing first and researching later. You already know what you want to say, so start by saying it. Then you can go through and see where you need support from scientific studies or interviews. I went through chapter documents and added the parenthetical [TK RESEARCH]. (In journalism, TK stands for “to come,” and is used because the letters t and k do not appear next to each other in any words in the English language, so if you do a command + F for “tk,” you’re just going to find the blanks to fill in, and never the word “bitchy.”)

I hired a research assistant towards the end (it was my friend Jess, who is also really super IN the book, so there was no objectivity involved) to intentionally find data to support things I knew to be true but couldn’t immediately source. Like: I wanted as many studies I could find about the disparity in mental health services for BIPOC individuals. The research is there, but it’s all over the place. She made a spreadsheet for me linking to the most relevant studies.

Could I afford a research assistant with the money from the advance I received? Absolutely not! But I weighed the amount of time I needed to spend researching against the amount of time I actually had, and decided that it would be a good investment in my mental health to pay out-of-pocket. Writers will generally tell you that there’s a lot you pay for out-of-pocket to make your book happen the way you want it to happen. Most of us write books because we love books; not because we expect to make money.

Writing The Draft

The first draft of KIN took, all in all, four years to write. A lot of that time was the wandering, flirting, falling-in-love-with-the-idea phase. I wanted to write this book so badly that it felt almost impossible to begin writing it. I was afraid that if I tried to hold the idea with my bare hands, I would kill it — like when you touch a butterfly and the oil from your fingers disturbs the dust on its wings and it can’t fly and it dies. (If I have just ruined butterflies for you, you’re welcome.)

I had to force myself to work on it in hour-long intervals. (Pro tip: if you’re having trouble showing up to the page, you’re setting an unrealistic goal for yourself in terms of time or word count. Start with 20 minutes or 200 words, and don’t let yourself go over.) Even that felt hard; I had to go to coffee shops, because there I would be forced to face my own fear of the book, rather than procrastinate to organize, for the 90th time, the box of love letters I kept from my high school boyfriends. (SADLY, THIS EXAMPLE IS REAL.)

Over time, the hour-long intervals became biweekly three-hour intervals. Early on, I sent chapters to Jill to compliment. I organized all my writing in Google Docs, which I greatly prefer to Scrivener for ease-of-use. I wrote a superlong outline that listed everything the book could possibly include, and linked scattered Google Docs to the corresponding outline areas.

I kept all my documents throughout the whole process in a simple Google Drive folder that looked like this:

But I mostly just used the outline doc (which evolved into something shorter and cleaner as time went on) to navigate my weekly writing.

A trick Jill taught me when I was writing my first book: never stop when you’re stuck. Only stop when you know exactly what you’re going to write next. Then leave yourself a quick note about what you’re going to start with next time. Then when you sit down to write again, you’ll be able to hit the ground running.

Receiving The Edits

After the first draft was finally done, I sent it off and braced myself. The first round of edits, for every book I’ve written, is universally humbling. The editors say nice things first, because they are very good at their jobs (and a quick shout-out here that my editors at Atria were top-notch; truly professional and brilliant), but then they get into how the whole thing is going to have to change dramatically.

In some ways, the hard part is done. You have a draft. People have seen the draft. The book is pinned to the table, and it can’t possibly escape. In other ways, the hard part is right now. Your skin must thicken, and you have less time than you need to break all the bones of your manuscript and suture them back into a new and improved shape.

For my first book, the edit was, “Totally restructure it.” For my second book (the audio book), the edit was, “This is too dry and needs way more of your voice.” For my third (a graphic memoir), the edit was, “We know drawings take forrreeeevvvvvver but you need to re-draw a ton of them.” And for this book, the edit was, “This book is only 50,000 words. We need you to write 25,000 more.”

What made this easier was that the editors (Stephanie Hitchcock and Karina Leon) clearly labeled parts where I could expand and add new thoughts and information. Rather than a total restructuring, I got to take what I had and bulk it up. It’s also easier to add than to cut; losing big swaths of book that you’ve worked really hard on is a blow, though it’s definitely part of the process. The “kill your darlings” of it all.

The Final Sprint: A Blitz

To write 25,000 words in a month while still working full-time, I had to let go of everything in my life that kept me grounded and sane. Look: I don’t think this is a good thing to do regularly. It makes you sick; it negatively affects your relationships; it is dangerous to your mental health and wellbeing. But we all are sometimes in this kind of pinch, and we are stronger than we know.

I took a machete to my schedule and cut out yoga, running, seeing friends, reading other people’s books, listening to podcasts, cleaning my house, publishing my chicken newsletter (yes, this is a thing I do), saying yes to lucrative freelance projects, coaching clients, going to meetings, eating lunch, sleeping sufficiently, meditating, journaling, keeping up with my Substack, and taking the train. I kept only my job, therapy, parenting, and dinner. I was very unhappy. But still, I knew it was temporary, and I was singularly focused: with any fragment of time I had, I wrote the book.

I kept a Notes App note documenting the number of words I was able to write every day. I noticed that as I defaulted to writing, I naturally improved at it; I got faster and slipping into flow came more readily. Ultimately, I wrote the 25,000 extra words in under two weeks. These were the two weeks where I wasn’t teaching; it was winter break. I knew this was important, empty-ish time, and I seized it.

So, look: the lesson is that a human can do this kind of thing once in a while. I did get sick pretty much immediately after I was done with the manuscript. I got winded walking up the single flight of stairs to my bedroom. I stopped feeling close to any of the moms at T’s daycare, where I used to feel a part of an important community. I lost touch with you — another community that’s come to mean so much to me. As soon as I was through with the book, I was back to teaching full-time, and I came into the semester with a totally empty gas tank: something you really shouldn’t do when you’re driving a car (a student newspaper) through a dark, swampy, toxic, sludge-swamp (a presidential administration threatening to deport students who write dissenting viewpoints in student newspapers).

But I’m so proud of the book. I could do it because it mattered to me in a way that nothing I’ve made before has. I want this book — and the stories in it, many of which include some of you — to make its way to other people who are running on empty. I want it to be fuel. The sprint was worth it.

After Every Step, A Treat

Every time I cleared one of these major hurdles in the process — additionally, adding the initial copy edits, finishing the massive bibliography, reaching out to the potential blurbers — I went to see April to get a pedicure. Each time, I brought a copy of Real Simple and read it cover to cover. This was a ritual, and April now congratulates me when I come in because she knows that I am there because I did something I am proud of.

And Now: The Cover

I went to April after the cover was finally done, because that, too, took such a long time to get through. There were so, so, so, SO SO SO SO many drafts of it. But ultimately, here it is. There was a time it was light blue, dark blue, pink. In the end, it is green. Because kinship is something you grow.

Housekeeping:

I mentioned Jill Riddell a lot throughout this post, and it’s possible that the main takeaways you have about writing were really from Jill. (Same.) She’s the founder of the

, which has a craft newsletter I contribute to called . We also host (free!) monthly in-person cowrites in Chicago; the next one is June 4 at 4 p.m.! Respond to this email and I’ll send you all the details.Another bullet point because Jill’s podcast, “The Shape of the World,” is entering its sixth season! Jill is a genius and this science-y podcast is truly delightful. Listen here!

I had an illustration in

, a Substack about the injustices of the American healthcare system. See it here, and stay for the rest of the stories and drawings!Now that my book is done-ish, I’ll be writing more newsletters and offering more paid content! Now’s a great time to up your subscription!

Loose Thoughts:

You guys, I am lying in my bed naked right now because I’ve just taken a shower because my nose was cold (my nose feels cold ALL THE DANG TIME), and as I lie here, there is a very exciting and rare yellow-throated warbler in the tree right outside my window, and I have to say this NEVER HAPPENS, I always WANT IT to happen, but it doesn’t. So this is a big deal and you are here for it.

I actually hear tons of warblers out there; I’m itchy to go out and see if I can see some.

I feel that something is going on with barrel-leg jeans. Like, I see people wearing them all the time, and I’ve seen memes about them. But then there are other people who are like, “what-legged jeans?” Are millennials the ones buying these? Or other people? Do you have some? Do you like them?

What is YOUR favorite bird? Please drop answers in the comments.

My birthday is on Saturday! I won’t probably talk to you before then. My sister will be in town with her family! I can’t believe another year has passed, but this time of year is a great reminder that summer is on its way for the Northern Hemisphere. I’m here for it.

Since I wrote that last bullet point, I went outside to try to photograph some birds, which was foolish, because I don’t know how to do it. But my husband is really good at it, so I get to enjoy seeing what he can do. Instead, I just had a lovely time in the sunshine feeling lucky to be alive.

NEW BOOK NEW BOOK

(1) "Back then, I could order a calzone and eat it under the covers as soon as I got home. (Which I did, four times per week.)" — that's good living right there.

(2) Wait, there's a chicken newsletter....?!

(3) I saw a male indigo bunting once in 2011. It was such a magical experience that I still think about it regularly.